The Time I Went in Search of the White Rajahs of Sarawak

There are times in life when you can find yourself humming along to David Byrne’s famous lines…

And you may find yourself living in a shotgun shack

And you may find yourself in another part of the world

And you may find yourself behind the wheel of a large automobile

And you may find yourself in a beautiful house

With a beautiful wife

And you may ask yourself, well

How did I get here?

Well, I wasn’t in a shotgun shack exactly - whatever that is… But I was in Kuching, the capital of Sarawak. And there were times when I did wonder how the hell I got there - maybe because I originally went there fascinated by the story of the White Rajahs - a family from Dartmoor, who literally became emperors.

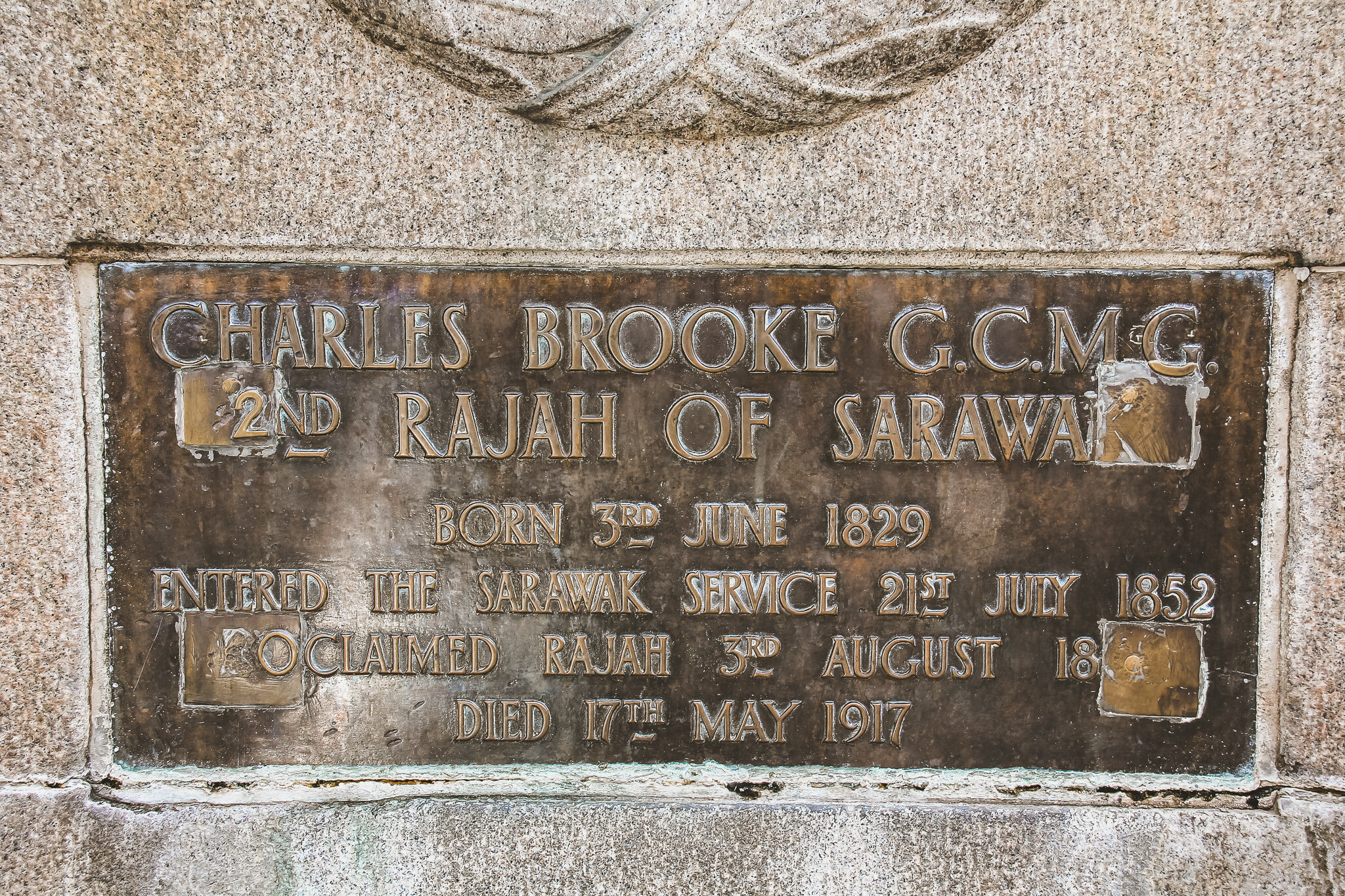

And I found a plaque, and a bar with the Brooke name attached.

But I enjoyed a great many adventures getting to see those two unmemorable things…

Later I wrote the article bellow in which you can learn all about the White Rajahs from Devon - but my adventure was one of several trips I’ve been lucky enough to enjoy in Malaysia and its islands. This one began with the most amazing firework display I’ve ever seen - it went on and on for many hours - which was a bit of a waste on me because I am not the most ardent fans of pyrotechnics.

But there were a lot of other things to enjoy, first in mainland Malaysia, then off to the south in Borneo where the White Rajahs used to rule the roost. Food being one thing. Lots of interesting food like sea-cucumbers and edible jelly fish.

And then there was the strange sometimes rather little city of Kuching. I like the place and had lots of fun visiting amazing restaurants and bars before heading off into the high jungle…

There are three graves tucked away in a corner of a lonely Dartmoor graveyard which represent one of this region’s greatest ever stories. The tombs contain the remains of three kings who had the power of life and death over countless thousands. Collectively the men who lie there are known as the White Rajahs.

Many West Country folk interested in the region’s history will have heard of them and perhaps know a little about the remarkable Brooke family - but there is no way anyone could understand just how big their story is without going half way around the planet to visit distant Sarawak.

the hills above Sheepstor on Dartmoor which was the real home of the White Rajahs

It is now one of two Malay states on the vast island of Borneo, but Sarawak used to be kingdom of the Brookes - and to this day their name survives long, loud and highly conspicuous in that distant, hot, humid, rain-forested land.

Go to Sarawak’s capital, Kuching, as I did recently and you will see evidence of the Brooke dynasty everywhere. There are streets and roads named after the family, trendy bistros bear their name, dockyards, boats, bridges, roundabouts, institutes... Indeed just about everything imaginable that has some kind of public face or input will have at least one example named Brooke.

And if the Brooke title doesn’t do it then there are places named after the Christian names of the three White Rajahs - James, Charles and Vyner - who all now lie in peace in the graveyard of St Leonard’s Church at cool and quiet Sheepstor.

But it’s not just in the physical presence of place names that the Brooke dynasty remains highly conspicuous in Sarawak. It’s right there at the heart of the way in which people think and talk about their country.

You hear constant reference to the “Brooke Era” or to the “Post Brooke Era”. For Sarawakians the dynasty remains a much more important part of everyday life than, say, our own historical link with the Tudors - or even, nowadays, to our referencing of concepts like “post-war Britain”.

The men who rest at Sheepstor were everything to Sarawak. They ran it, they built it, they extended it - they just about invented it.

In the past dozen years writing for this newspaper I have referred to the White Rajahs on numerous occasions, simply because I’ve always been in awe of the pure exoticism of their story - but never did I imagine they held such massive sway over an entire nation.

When I was invited to Sarawak by the Malaysian government recently to take a look at the eco-tourism they’re developing in the magnificent rainforests there, I promised myself I’d grab the chance to follow in the footsteps of the White Rajahs and put aside some time to see if any trace of them remained.

There was no delving necessary. As I say, I was confronted by Brooke-this-that-and-everything-else the moment I entered the small and charming city of Kuching.

I say small, but the place is beginning to sprawl in the most anarchic and materialistic of ways – the sort of thing none of the Brooke’s would have ever allowed. They were a disciplined and controlling trio - nothing much happened in the 105 years they ruled the roost there that they didn’t create, inspire, ban or veto.

After talking to various people in Sarawak I think you could say that the Brooke Dynasty could otherwise be described as a benign dictatorship. They controlled everything - sometimes with a rod of iron, sometimes with violence - but they did it for the general good.

And I came away with the impression that, although no such dynasty would be welcome now, the Brookes are generally regarded as having been a good thing rather than out-and-out bad - and that their form of colonial imperialism, though riddled with faults, eccentricities and failures, helped establish Sarawak to be the rather civilised place it is today.

So who were these people who’ve now turned to dust in deepest, dampest, Dartmoor - and how on Earth did they get to be monarchs of such a distant land? The story has been written many times before - in fact there are even references to it in famous tales like The King and I and Joseph Conrad’s novel Lord Jim. is said to be based on James Brooke, the first White Rajah - and, believe me, by the end it had all become very eccentric and colourful indeed.

But here’s a brief outline of what must be one of the best ever tales to be related to the West Country: just under 200 years ago James Brooke was trying his luck as a trader in the Far East, and not doing particularly well at it. But in 1833 he inherited £30,000 - a vast sum back then - and he spent some of the money on a 142-ton schooner called The Royalist.

Five years later he was in Borneo where he found the town of Kuching facing a tribal uprising - he promptly offered to help the Sultan of Brunei and, with his crew, was able to help bring about a peaceful settlement. The Sultan was impressed and - to cut a long story short - eventually offered Brooke the title Rajah of Sarawak after the Englishman had threatened him with military force to come good with his promise.

Once Brooke was on the throne, he wasn’t about to give it up - on the contrary, he set about extending his influence and his domain. He formed a proper Western-style administration and civil-service, drew up laws and fought piracy which was endemic in those parts. In 1847 Brooke returned temporarily to England where he was granted all manner of great honours - and also given an estate at Burrator on Dartmoor as a thank you from a grateful British nation for his work in enlarging our influence in the Far East

Back in Sarawak, Brooke took charge of what amounted to 3,000 square miles of swamp, jungle and river, much of it populated by various tribes who were basically still living in the Bronze Age. They marked important events in their lives by taking the heads of other people in the community. If a Dayak husband failed to present a human skull to his wife after the birth of a child then it was feared that the newborn would meet with illness or even death.

Likewise, no young Dayak warrior ever went courting without first donning an animal mask and skins and ambushing a fellow, often a woman or child from his own community. He then made his intended a present of his victim’s skull.

Such acts were quickly outlawed by Brooke - as the new nation’s self-appointed judge, he presided over court sessions in the front room of his own house, a hastily assembled plank-and-thatch affair in Kuching.

With his pet orang-utan, Betsy, scampering around in the background, the legal proceedings attracted much interest in Sarawak, although not for the reasons Brooke had intended. For many, the main draw was the opportunity to place bets on the fate of those on trial including, in one bizarre case, a man-eating crocodile.

This creature stood accused of killing a court translator who had toppled drunkenly into the river one night and, after much weighing of the arguments for and against its punishment, Brooke solemnly recorded the verdict in his journal: “I decided that he should be instantly killed without honours and he was dispatched accordingly; his head severed from his trunk and the body left exposed as a warning to all the other crocodiles that may inhabit these waters.”

Brooke never married - indeed, Google him today and you will find mention of his rather worrying liking for very young men - but before his death in 1868 he nominated as heir his sister’s son Charles Johnson, a former sailor, who changed his surname to Brooke upon becoming Rajah.

A beneficent and much-loved ruler who was 39 when he came to power, Charles extended the boundaries of the land under his control into the interior until Sarawak was the size of England. He also abolished slavery and built roads, waterworks and even — in the style of a true Victorian — a railway.

He also encouraged his British officers to take native women as lovers in the hope that they would become ‘sleeping dictionaries’ who could teach them the local language. But at home he was somewhat less easy-going. Charles was “a queer fish” according to his British wife, Margaret - an understated description of a man who had lost his eye in a hunting accident and replaced it with a glass one, taken out of a stuffed albatross.

Charles did all manner of odd things – for example he forbade his sons to eat jam because he deemed it effeminate. His marriage became strained after he killed his wife’s pet doves and served them in a pie for her supper one night.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Margaret spent much of his 50-year period of rule back home in England - seldom seen without a green parrot perched on her wrist, she lived in a house near Ascot called Greyfriars and became obsessed with finding wives for their three sons.

She did so by inviting eligible young women to join them in forming a musical ensemble known as the Greyfriars Orchestra. Among those attending the first rehearsal in 1902 was the Honourable Sylvia Brett — daughter of the 2nd Viscount Esher — later to become known by newspapers of the day as Sylvia, Queen of the Headhunters.

Although she had no musical skills, Sylvia’s contribution to the Greyfriars Orchestra was as a percussionist. She obviously performed with beguiling effect, because one day the Brookes’ eldest son, Vyner, then 28, made his move, asking if he might tune her drum. A subsequent courtship resulted in their marriage in February 1911, after which they set sail for Sarawak

By then, the Rajah’s Palace was an imposing affair, perched on a hill overlooking the river in Kuching and comprising three airy bungalows with wide verandahs. The couple would sleep through the afternoon, then have tea and play tennis or golf in the cool of the evening.

It might have been an idyllic existence living there as son and daughter-in-law of the Rajah, had Sylvia produced a son to ensure the succession. She became pregnant almost immediately, but the child she gave birth to in November 1911 was a girl — much to Rajah Charles’s disappointment.

The following year, however, he received news from England that filled him with joy. His second son Bertram had married Gladys Palmer, an heiress to the Huntley & Palmers biscuit fortune, and she had a boy called Anthony who would serve as an heir if Sylvia failed to produce a son for Vyner.

Sylvia went on to have two more daughters, but no sons - and the antics of Princesses Gold, Pearl and Baba, as they were nicknamed by locals, would for decades fascinate the press in both Europe and America.

By the 1930s Sarawak had become something of a music-hall joke and as he grew older, Vyner (who’d succeeded his father Charles) appeared to lose interest in the day-to-day business of government and considered abdicating.

Since his brother Bertram had suffered a nervous breakdown and was incapable of rule, his natural successor was his nephew, Anthony. In 1939, during one of Vyner’s annual pilgrimages to England for the flat-racing season, the 23-year-old heir apparent was left in charge of the country for six months, but was never made Rajah.

He made a good impression on the British Colonial Office, despite his aunt Ranee Sylvia accusing him of inflated self-importance. She reported, among other things, that he had attached a gold cardboard crown to his car and ordered ox-carts and rickshaws to draw aside as he passed.

He denied these charges, but he was never allowed to inherit the rule of Sarawak because in 1946 Vyner agreed to cede it to the British Crown in return for a substantial financial settlement for him and his family. So it became Britain’s last colonial acquisition - and by then it was a broken nation having endured some of the worst horrors of the Japanese empire building in the Second World War.

After failing in a long legal battle to have the sale of Sarawak reversed, Anthony began a second career as a self-styled ‘ambassador-at-large for the people of the world’, travelling the globe and campaigning for peace.

By then all three White Rajahs were lying in their final resting place at Sheepstor. Go there now and it is quite impossible to understand or imagine what power the three men had on the exotic and distant nation which is now part of Malaysia.

Likewise, if you describe their modest Dartmoor burial plot to people in Sarawak they will gaze at you in disbelief. My rainforest guide Henry was appalled: “Surely,” he said, “the Brookes have tombs in one of your great cathedrals?”

He couldn’t believe the photographs I showed him of Sheepstor. It is the very antithesis of the hot jungle where the Brookes held so much sway for 105 long, sweaty and eccentric years.